Yifan Xiang

12/12/2024

word count: 2174

Introduction:

This article is a source review on postcolonialism. It explores and illustrates the cultural shocks brought to the Western world by postcolonialism theory during the mid-20th century. The emergence of this perspective represents self-reflection and self-critique of Western culture, as it originates from within the framework of Western cultural systems.

Many views suggest that postcolonialism is centered around the narratives and ideologies of capitalism. Marx, in his Critique of Political Economy, introduced the concept of the “Asiatic Mode of Production” and was among the first to recognize the cultural and ideological differences between the East and the West, as well as their differing understandings of colonization and subjugation.

This article primarily introduces the emergence of postcolonial theory, its development to date, and its impact on design.

Part I

Postcolonialism is a broad and profound concept that emerged in Western societies after World War II. It represents a reflection on colonialism, aiming to critique the relationships between colonizers and the colonized, as well as the cultural identity and community interactions within colonized regions. To understand postcolonialism, it is essential to clarify its concept. As Mishra, Vijay, and Bob Hodge mention in their work ‘What Was Postcolonialism?’, postcolonialism is a fluid concept that evolves over time and is influenced by various factors.[1] Therefore, our narrative exploration of postcolonialism should not be confined to a single period; instead, we must consider its entire development.

Similarly, the term “postcolonialism” is inherently ambiguous, encompassing both the continuation of colonial history and new modes of cultural analysis. In postcolonial studies, efforts to refine its definition are ongoing. For example, in the SETTLER COLONIALISM, it is noted: “It is both as a complex social formation and as continuity through time that I term settler colonization a structure rather than an event, and it is on this basis that I shall consider its relationship to genocide.”[2] This highlights that racial relations are an indispensable aspect of defining postcolonialism. They represent a structural narrative of decolonization for the colonized, which is a key element of postcolonialism.

In the process of decolonization, postcolonialism must analyze the new cultural narratives of the colonized (often referred to as Indigenous peoples) regarding the colonizers, as well as how they reclaim their original culture during this process. Furthermore, it is essential to study these cultures in the postcolonial, identifying and developing analytical frameworks unique to the Indigenous cultures themselves.

Furthermore, the definition of postcolonialism extends beyond its structural aspects to encompass its interpersonal dimensions. As E. Tuck and K.W. Yang argue in Decolonization is Not a Metaphor:

The other form of colonialism that is attended to by postcolonial theories and theories of coloniality is internal colonialism, the biopolitical and geopolitical management of people, land, flora and fauna within the “domestic” borders of the imperial nation. This involves the use of particularized modes of control – prisons, ghettos, minoritizing, schooling, policing – to ensure the ascendancy of a nation and its white elite. These modes of control, imprisonment, and involuntary transport of the human beings across borders – ghettos, their policing, their economic divestiture, and their dislocatability – are at work to authorize the metropole and conscribe her periphery. Strategies of internal colonialism, such as segregation, divestment, surveillance, and criminalization, are both structural and interpersonal. [3]

The sense of identity and community belonging among the colonized becomes fractured in the post-decolonization. This fragmentation arises because colonizers controlled fundamental institutions such as schools and hospitals. In the journey of decolonization, there exists a dialectical relationship between cultural analysis and interpersonal interactions.

In the postcolonial, some individuals struggled to reintegrate into their local communities because they have lost the cultural frameworks of their original communities. During colonial times, the colonized developed an understanding of the colonizers’ knowledge systems, values, and identity constructs that diverged from their own cultural analysis. This divergence has led to a sense of disconnection from both cultural and identity perspectives in the postcolonial period, illustrating the interpersonal of postcolonialism.

The definition of postcolonialism is dynamic and ambiguous, yet it has profound and lasting impacts on people in colonized regions. These impacts are not only structural but also interpersonal. The debates surrounding postcolonialism remain contentious, reflecting its complexity. Postcolonialism is not merely a product of self-reflection within the Western-centric world but also an atypical narrative of decolonization.

There is a perspective that argues postcolonialism does not need to be abolished, as it represents a manifestation of modern globalization. This view highlights cultural expansion and the globalization of capital as concentrated expressions of modernity. As Aijaz Ahmad posits[4], the process of modernization is inevitable, and the West’s position as a cultural center is merely incidental. There is no need for guilt or self-criticism over the West’s cultural dominance, as the primary driving force in history is rooted in capitalist modernity and globalization. Besides, globalization and modernization are seen as inevitable outcomes—processes that have already occurred or are currently unfolding and are irreversible. Consequently, postcolonialism, within the trends of globalization and modernization, is an inevitable phenomenon. In other words, postcolonialism represents a definitive transformation within the framework of capitalist modernity.

At the same time, E. Tuck and K.W. Yang argue that the development of postcolonialism is fundamentally rooted in anti-colonialism. Postcolonialism should explore and examine how local populations in the aftermath of decolonization integrate aspects of colonial culture while restoring their own. As mentioned in Decolonization is Not a Metaphor:

“However, an anti-colonial critique is not the same as a decolonizing framework; anti-colonial critique often celebrates empowered postcolonial subjects who seize denied privileges from the metropole. This anti-to-post-colonial project doesn’t strive to undo colonialism but rather to remake it and subvert it.” [5]

The exploration of postcolonialism, therefore, should focus on how the colonized subvert and reshape colonial cultures to rediscover their narrative identity and cultural analysis rooted in their own ethnicity. It should not center on self-critical reflections of colonialism from a Western perspective but instead seek to understand the processes of cultural reclamation and redefinition by the colonized.

In contrast, Ahmed argues that since postcolonialism is both structural and interpersonal, it cannot be regarded as a necessary condition for postmodernity and modernity. As Ahmed notes:

“To make such an argument is not to say that we can only understand such historical transitions in terms of colonialism – I am not seeking to reverse the terms of Ahmad’s version of Marxism, by making colonialism primary and capitalist modernity secondary. What is crucial is that the colonial project was not external to the constitution of the modernity of European nations: rather, the identity of these nations became predicated on their relationship to the colonised others. This is one of the significant theoretical contributions made by those working on postcolonialism, and its implications are far-reaching.“ [6]

Ahmed’s perspective directly opposes Aijaz Ahmad’s view. He contends that colonialism’s prerequisite was the identity construction of the colonized populations. European modernity, in this interpretation, was intrinsically tied to its colonial relationships, with these relationships fundamentally shaping national identities rather than being external influences.

Anas M. Alahmed introduces a political dimension to this perspective, emphasizing that postcolonialism represents a political struggle transitioning from dependency to sovereignty. After the struggle ends, local elites often emulate their former colonizers, positioning themselves as a distinct, superior class separate from the general populace. As Alahmed explains in his article Internalized Orientalism: Toward a Postcolonial Media Theory and De-Westernizing Communication Research from the Global South:

“Thus, the ruling and elite classes in the postcolonial states construct themselves as the Self by attributing the inferior aspects of the local culture to the rest of the society, who becomes the Other. The designation and identification of the Other demonstrates the same representational strategies deployed in the historical Western stereotyping process, with the elites depicting themselves as modern, civilized, and progressive.“ [7]

The elite class, in pursuing an identity distinct from the local masses, abandons the analysis of their indigenous identity, instead conforming to Western stereotypes of modernity and progressiveness. This alignment with Western ideals diminishes the focus on identity analysis among those self-identified as elites within postcolonial societies, undermining the narrative authenticity of local culture.

Thus, in the process of decolonization, postcolonialism reflects the atypical cultural analysis of the elite class within the theoretical struggle of transitioning from political dependence to sovereignty. It also highlights the negative cultural impacts on the broader colonized population, as elite conformity to Western norms disrupts and dilutes the typical narratives of local cultural identity.

Part II

Understanding the contemporary development of postcolonialism reveals its immeasurable impact across various fields, including design. Postcolonialism leans toward structural narratives while also carrying humanistic attributes. These include the colonial biases imposed by colonizers on the societies of the colonized and the post-decolonization efforts to reclaim identity and rebuild community belonging.

For designers, this understanding is crucial. As Egbers, Vera, Christa Kamleithner, Özge Sezer, and Alexandra Skedzuhn-Safir state in Architectures of Colonialism: Constructed Histories, Conflicting Memories:

“This is likely to uncover great injustices but, rather than freezing with potential culpability, this finer resolution and critical distance will hopefully lead to more sensitive and integrated design work. With this inventory – albeit imperfect – the designer must set to work.“ [8]

Design sits at the intersection of critique and creation, serving as a tangible embodiment of human consciousness. It is omnipresent in daily life and must not shy away from engaging with structural narratives for fear of criticism. Instead, designers should embrace the potential of cultural analysis embedded within postcolonial contexts to produce work that is more sensitive, integrated, and reflective of diverse identities and histories.

In design, the composition of design elements reflects the designer’s understanding of the identity analysis of the colonized in postcolonialism and the replacement narratives for local colonial culture. Designers need to consider what kind of identity conflicts and community belonging inconsistencies the design elements might bring to users.

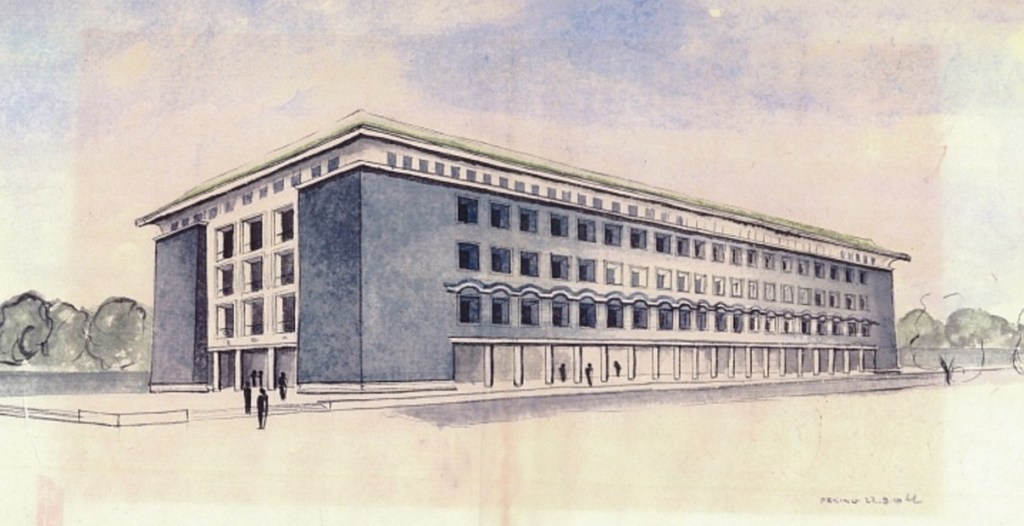

For example, Haus des Handels in Beijing is a design proposal from the early days of China’s founding(Imag1[9]). At that time, the designers aimed to reduce Western-centric design concepts by minimizing the most distinct structural features of Bauhaus in the building, instead incorporating traditional Chinese elements into the architectural design. This was intended to enhance the local residents’ identity analysis and provide them with a sense of familiarity and community belonging when encountering the new architecture.

This approach has profoundly influenced the design and aesthetic trends in mainland China over the past ten years. For example, Wuhan University’s library (Image2[10]) is a good continuation of this style, striking a balance between identity analysis and community belonging. This reflects the designer’s effort in postcolonial narratives to find a middle ground between people’s identity analysis and their sense of belonging.

In the field of postcolonial design, one of the most criticized aspects is the designer’s approach to addressing the identity recognition and structural narratives of local residents. This also reflects a form of self-reflection and concrete action by the local residents (the colonized) in examining and responding to their own identity. As Chambers, Iain writes in The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History:

“Significantly, postcolonial art often manifests itself in forms of desiring and untamable forces, in expressions of interconnections, border-crossing, becoming.” [11]

The same applies to design. It often seeks to integrate Western values and aesthetics with local aesthetics and narratives to create new architectural and design styles. This process is both bold and narrative-driven, representing an effort to merge different cultural perspectives into innovative design expressions.

Conclusion

This literature review encompasses the theory of postcolonialism, its development to date, and its manifestations and applications in design. During the developmental stages of postcolonial theory, it has undergone gradual refinement. First, its definition was established as fluid and evolving over time. Subsequently, structural and interpersonal dimensions were incorporated into the theory.

To date, two distinct perspectives on postcolonialism have emerged. The first posits that postcolonialism is an inevitable result of modernization, with the West’s centrality being incidental. From this perspective, postcolonialism represents an inevitable trend of modernization and globalization.

In contrast, the second perspective argues that postcolonialism should prioritize the identity recognition of local residents as a prerequisite, integrating the conflicts between colonizers, the colonized, and social classes. This view asserts that if postcolonialism is both structural and interpersonal, it should not be considered an inevitable product of modernization and globalization.

At the same time, in the field of design, postcolonialism has significantly influenced design elements. It abandons the traditional Western-centric design approach, shifting toward integrating a greater proportion of local artistic elements into Western design foundations. Postcolonial design incorporates local residents’ identity analysis of their culture and an atypical aesthetics of structural narrative.

[1] Mishra, Vijay, and Bob Hodge, In the beginning was the word, “What Was Postcolonialism?” New Literary History, vol. 36, no. 3(2005), pp. 375–402. P 377,

[2] PATRICK WOLFE, Journal of Genocide Research, Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native (387-409), P. 390

[3] E. Tuck & K.W. Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40, P. 5

[4] Aijaz Ahmad. In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures, London: Verso. (1995) ‘The Politics of Literary Post-Coloniality’, Race and Class 36, 3: 1–20

[5] E. Tuck & K.W. Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor, P19

[6] Sara Ahmed, introduction, Strange encounters embodied others(Routledge: 2000), P.10, <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203349700 >

[7] Anas M Alahmed, Internalized Orientalism: Toward a Postcolonial Media Theory and De-Westernizing Communication Research from the Global South, Communication Theory, Volume 30, Issue 4, November 2020, Pages 407–428,

[8] Egbers, Vera, Christa Kamleithner, Özge Sezer, and Alexandra Skedzuhn-Safir, Architectures of Colonialism : Constructed Histories, Conflicting Memories., 1st ed. (Basel/Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2024) <https://doi.org/10.1515/9783035626704>

[9] Wolfgang Thöner, Bauhausmoderne und Chinesische Tradition Franz Ehrlichs Entwurf für ein Haus des Handels in Peking (1954–1956) (03.July.2018), <https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/1086/bauhausmoderne-und-chinesische-tradition>, (accessed 09/12/2024)

[10] Wuhan University, < https://en.whu.edu.cn/info/3941/43081.htm >, (accessed 09/12/2024)

[11] Iain Chambers, The Postcolonial Museum : The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), introduction, page 3

Bibliography

Ahmad, Aijaz. In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures, London: Verso. (1995) ‘The Politics of Literary Post-Coloniality’, Race and Class 36, 3: 1–20

Alahmed, Anas M, Internalized Orientalism: Toward a Postcolonial Media Theory and De-Westernizing Communication Research from the Global South, Communication Theory, Volume 30, Issue 4, November 2020, Pages 407–428,

Ahmed, Sara, introduction, Strange encounters embodied others(Routledge: 2000), P.10, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203349700

Chambers, Iain, The Postcolonial Museum : The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), introduction, page 3

E. Tuck & K.W. Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40, P.5 ,P. 19,

Egbers, Vera, Christa Kamleithner, Özge Sezer, and Alexandra Skedzuhn-Safir, Architectures of Colonialism : Constructed Histories, Conflicting Memories., 1st ed. (Basel/Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2024) https://doi.org/10.1515/9783035626704

Mishra, Vijay, and Bob Hodge, In the beginning was the word, “What Was Postcolonialism?” New Literary History, vol. 36, no. 3(2005), pp. 375–402. P 377,

Thöner, Wolfgang, Bauhausmoderne und Chinesische Tradition Franz Ehrlichs Entwurf für ein Haus des Handels in Peking (1954–1956) (03.July.2018), <https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/1086/bauhausmoderne-und-chinesische-tradition>, (accessed 09/12/2024)

WOLFE, PATRICK, Journal of Genocide Research, Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native (387-409), P. 390

Wuhan University, < https://en.whu.edu.cn/info/3941/43081.htm >, (accessed 09/12/2024)