YIFAN XIANG

20/09/2025

During the decline of the Qing dynasty, China went through an extremely chaotic period. Events such as the First Sino-Japanese War, the Opium Wars, the Treaty of Shimonoseki, the Boxer Protocol, and the invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance inflicted devastating blows on China in several respects—for instance, the authority of the imperial throne and the control of local powers. These upheavals indirectly led to the later turmoil of warlord conflicts.

Yet in other respects, these events also opened China’s doors to the outside world. With the country’s gates forced open, China began to fall into a semi-colonial and semi-feudal system. Traditional Chinese design and culture suffered significant impacts, especially among the upper classes of society. Prominent examples include cities such as Shanghai, Wuhan, Guangzhou, and the northeastern regions influenced by Japan and Russia.

Amid these influences, and with the Chinese government allowing foreign powers to establish colonies (commonly referred to as concessions), the architecture of many cities was deeply affected. For instance, the row of buildings along the Huangpu River in Shanghai, as well as structures within the British, French, and Russian concessions in Hankou—including the Dazhilu Railway Station—were all shaped by foreign cultural influences. Their designs followed the architectural styles of different nations, naturally extending to interior design and industrial design as well.

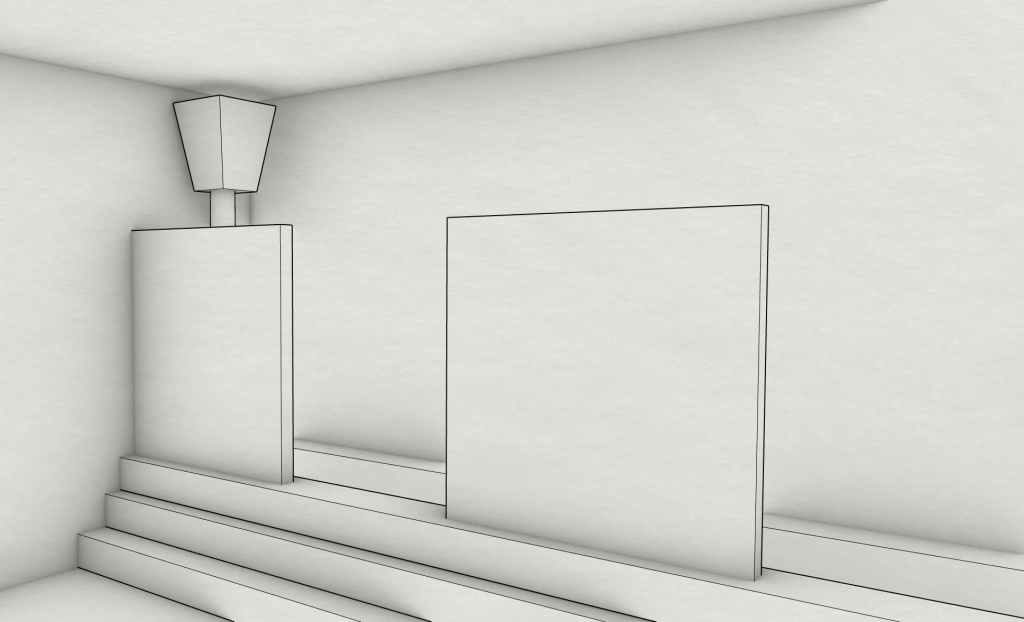

As illustrated in Figure 1, this photograph depicts the toilet used by Puyi, the last emperor of China, after his departure from the Forbidden City and subsequent relocation to Shenyang, where the Japanese provided him with a residence. In this image, numerous design features reveal the incorporation of Western stylistic elements, such as the picture frame on the wall, the framing of the mirror on the left, and the decorative carvings surrounding the bathtub.

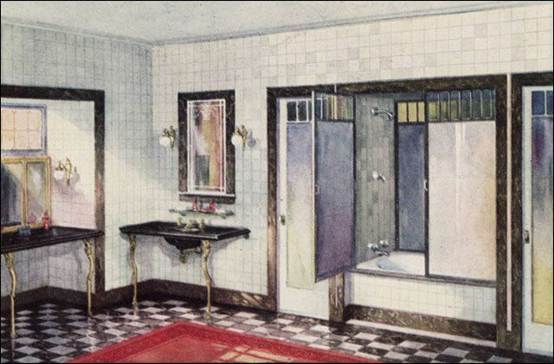

Within the interior layout of the toilet, Western influences are further evident. The flooring consists of small, patterned ceramic tiles, a style popular in the West at the time, while the walls are covered with plain white tiles. Comparable features can be observed in contemporary European and American design advertisements (see Figure 2). Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan sought both to disengage from Western domination and to establish itself as a strong competitor to the West. On this ideological foundation, the Japanese introduced localized modifications to Western design styles, including the reduction of excessive ornamentation, the consistent use of white walls, and the avoidance of contrasting colors or conspicuous patterns.

This tendency may be interpreted as a subtle compromise between Western traditional decorative conventions, the modernist interior design aesthetics of the West, and the Japanese sense of national confidence and identity. Within such a framework, the design of toilets and bathrooms frequently conveyed a sense of imbalance, echoing the observation noted in the previous chapter that “the toilet was always regarded as an appendage.” In Eastern contexts, toilet design continued to receive relatively little attention.

By contrast, the design of bedrooms and offices in China demonstrated a more coherent integration of traditional Chinese elements with Western classical aesthetics. This form of synthesis was rational, traceable, and based on an identifiable foundation, rather than, as in the case of toilet design, appearing rigid, awkward, and mechanically transplanted.

After the September 18 Incident, Japan initiated its war of aggression against China. At the same time, with the rise of a new bourgeoisie, China witnessed the emergence of an increasing number of domestic entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, due to the wartime context, relatively few records from this period have been preserved. Consequently, comparative analysis must be conducted with reference to other countries of the time.

For example, in the United States, sanitary design was also influenced by European models. However, owing to differences in decorative aesthetics, American fixtures generally did not feature prominent surface ornamentation. Instead, greater emphasis was placed on practicality, which led to significant advances in functionality. The United States was also among the first countries to implement the large-scale installation of urinals.

Part II: The Development of Toilets in the People’s Republic of China

With the conclusion of the War of Resistance against Japan, China gradually began to promote a movement of decolonization, although the process was at times rather intense. In the early years of the People’s Republic, the nation remained in a state of reconstruction. Following its founding, China sought to free itself from the cultural shadow left by the West. For example, in 1953 the Communist Party of China launched the First Five-Year Plan, which vigorously promoted the development of domestic handicraft and manufacturing industries, while also engaging in extensive technological and cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union, then a fellow member of the socialist bloc. At the conceptual level, this interaction also provided guidance for the subsequent construction of a non-typical postcolonial narrative framework.

However, in the realm of culture, the Soviet Union remained largely aligned with European traditions. As a result, in terms of toilet decoration (see Figure 4), Soviet influence did not significantly diverge from contemporary European practices. In both product design and the broader narrative surrounding toilets, little effective response was made to the postcolonial discourse that was emerging in China during the 1950s. At that time, nationalist sentiment in China was strong, and there was an eagerness to cast off the cultural constraints left by the semi-colonial past. Authorities sought to accelerate cultural decolonization through the promotion of national art. At the same time, this also laid the groundwork for the outbreak of extreme nationalist sentiment in the Cultural Revolution.

Meanwhile, Japan experienced considerable progress in its postwar economic recovery. During this period, the construction of public toilets in Japan began to exert an influence on the subsequent design of Chinese toilets. For instance, the squat toilet, as shown in Figure 5, became a significant feature. This example from a 1950s Japanese public toilet demonstrates that the overall form was already approaching the characteristics of modern Chinese toilets, with notable improvements in the shaping of the overall environment.

As the tide of Chinese nationalism intensified, the Cultural Revolution, often referred to as the “ten tumultuous years,” gradually unfolded. During this decade, many buildings and interior decorations from the colonial period were destroyed in a relatively short span of time. At the same time, Mao Zedong advocated that young people should “go up to the mountains and down to the countryside.” Consequently, during this period, ordinary citizens largely continued to rely on dry latrines (see Figure 6). Within this cultural atmosphere, the status of toilets in China reverted once again to the minimal function of providing a space for basic waste disposal.

Part III: The Development of Toilet Design after the Reform and Opening-Up

With the end of the Cultural Revolution, China began to adjust its policies and initiated a series of hygiene campaigns, among which the “toilet revolution” was of particular importance. During this period, the Chinese government increasingly prioritized rural sanitation, launching a number of projects to renovate village toilets. For a densely populated country like China, toilets were of critical significance: if the disposal of human waste was not properly managed, it could contaminate water sources and lead to epidemics and disasters.

In fact, as early as the founding of the People’s Republic, the government had begun to take the issue of public health seriously. However, due to limited financial resources in the early years, large-scale investment in infrastructure was not feasible. As a result, disease prevention at that time often relied on simple measures, such as the widespread campaign to “boil drinking water.” This practice later distinguished China’s drinking habits from those of Europe, the United States, Japan, and South Korea.

After the Reform and Opening-Up, large-scale commercial activities expanded rapidly, and the number of individuals benefiting from economic growth increased. By the 1970s and 1980s, more and more households began to install private flush toilets connected to sewage systems. At the same time, the construction of public toilets also gradually increased.

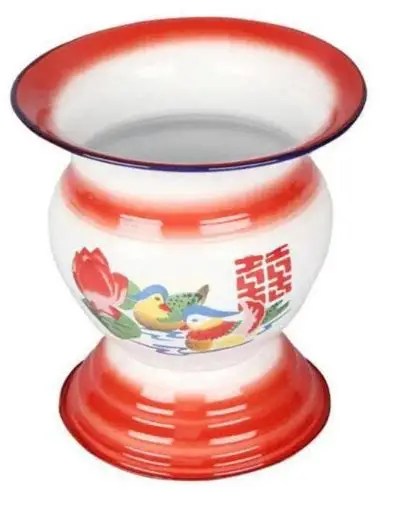

Nevertheless, in the early stages of the 1970s and 1980s, toilets did not yet receive sufficient attention. For example, among the urban lower and middle classes, many families still relied on buckets for waste storage. As shown in Figure 7, a common vessel sold at the time was known as a tanyu (spittoon), which was widely used for storing human waste (see Figure 8).

Entering the 1980s, as increasing numbers of foreigners came to China to engage in commercial activities, greater attention began to be paid to the design of toilets in high-end venues (see Figure 9). The example shown is a hotel that opened in China during the 1980s. It demonstrates that the interior design of toilets at the time largely remained at the stage of imitating earlier foreign models, without implementing effective separation of wet and dry areas, and with limited consideration given to privacy. Within such a design environment, the discourse of design language and the understanding of spatial narrative among Chinese designers were still at a relatively preliminary stage. As shown in Figure 10, which depicts a hotel guest room from the same period, designers were still imitating foreign models in their approach to toilet design. However, in terms of room decoration, the design styles of the time had already offered a meaningful interpretation of decolonization and postcolonial theory. Toilets, by contrast, received far less emphasis.

By the 1990s, toilet design gradually began to attract more serious attention. In newly constructed housing, it became increasingly common for each household to have a private toilet. This period also marked the rapid expansion of China’s large-scale infrastructure projects, including railways, high-rise buildings, and highways. The design styles of high-end hotel toilets from the 1980s, though not yet fully refined, began to spread into domestic settings. A distinctive characteristic was the widespread use of white square wall tiles and square ceramic floor tiles, often printed with intricate patterns depicting trees, flowers, or traditional landscape motifs.(figure 11)

Meanwhile, in the field of public sanitation, a new form of squat toilet system was developed. These toilets were connected below by a shared channel and flushed collectively at fixed times.(figure 12) At one end of the underground channel there was a large water tank, while the other end connected directly to the sewer system. This configuration typified public toilets in China during this period and was commonly found in schools or hospitals constructed in the 1990s.